Social connectedness improves public mental health: Investigating bidirectional relationships in the New Zealand attitudes and values survey

Authors

Alexander Saeri, Tegan Cruwys, Fiona Barlow, Sam Stronge, and Chris Sibley

Author affiliation

University of Queensland, University of Auckland

Publication

Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 52(4), p. 365-374, April 2018

Methodology

The research used four waves of the New Zealand attitude and values survey (NZAVS) dataset and a fully cross-lagged panel analysis to test three hypotheses:

- Social connectedness is a predictor of next wave mental health;

- Mental health is a predictor of next wave social connectedness; and

- The relationship between social connectedness and lagged mental health is stronger than the converse.

Results

All three hypotheses were supported. In particular, social connectedness is a more consistent and about three times stronger predictor of mental health year-on-year than the converse. "These results support a growing body of evidence that has demonstrated the importance of social connectedness in promoting and maintaining mental health in the general population."

Conclusion

The research provides the strongest evidence to date that social connectedness is a stronger predictor of mental health than the converse. "The findings speak to the value of interventions to improve social connectedness, such as facilitating engagement with existing group memberships and building new group memberships, for mental health.

“Social connectedness can act as a ‘social cure’ for psychological ill-health.”

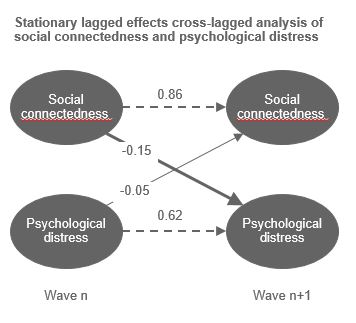

Relationship between social connectedness and psychological distress

In the research, mental (ill-)health was operationalised as psychological distress. The fully cross-lagged stationary panel analysis (see the figure) strongly predicts that someone socially connected will remain socially connected a year later (0.86) and less strongly predicts that someone in psychological distress is likely to still be in psychological distress a year later (0.62). For this research, the interest was in the cross terms. Lack of social connectedness (e.g. loneliness) predicts psychological distress a year later (-0.15) more so than psychological distress predicts lack of social connectedness (e.g. loneliness) a year later (-0.05).

In medical and psychiatric contexts, lack of social connectedness (or poor social functioning) is frequently considered to be an outcome of a mental health condition. Rarely is lack of social connectedness (e.g. loneliness) considered a risk factor for mental health and a point of early intervention. However, an implication of this research is that medical and psychiatric professionals should reconsider poor social health (e.g. loneliness) as a point of early intervention before more serious mental health issues develop. Furthermore, good social health provides a preventative measure for mental health.

A non-stationary model of the lagged relationships between social connectedness and psychological distress had a better fit than a stationary model – which suggested that the relationship may vary over time. However, the time-varying nature of the relationships could be caused by the Christchurch earthquake between waves 2 and 3, which caused psychological trauma for residents.